Read Time: 5 minutes

Readability: Advanced 📐 (Technical knowledge needed)

Core Topics: cat, quantum, state, box, measurement

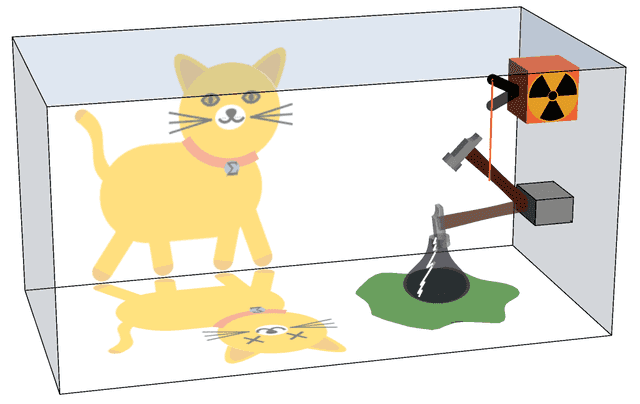

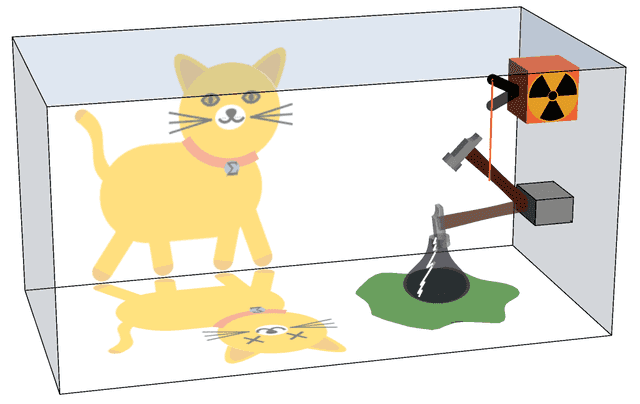

The concept of quantum superposition (or superposition for short) is very counterintuitive, as Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger noted in 1935 writing [1], “One can even set up quite ridiculous cases.” To make his point, he assumed a cat was closed out of sight in a box with a radioactive material that would decay with 50% probability within an hour. If a radioactive decay occurred, a deadly gas would be released in the box killing the cat. Since the decay was represented by a quantum wavefunction in a superposition of 50% “yes” and 50% “no” regarding the decay after one hour, the cat was also represented by a quantum wavefunction in a superposition of 50% “alive” and 50% “dead” (Figure 1). Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger wrote [1]:

The wavefunction of the entire system would express this by having in it the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) mixed or smeared out in equal parts.

This has become known as Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger’s Cat.

Figure 1 (taken from [2])

This is usually where the introduction of superposition via Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger’s Cat ends, but it doesn’t fully capture the weirdness of superposition. What’s the difference between superposition and simple ignorance about the state of the cat hidden from sight inside the box? What if my cat-killing trigger was classical instead of quantum, would that somehow change the situation from superposition to simple ignorance about the state of the cat? Suppose I give you a ride home and watch you until you disappear into your house. At that instant there is some non-zero probability that you will drop dead of a stroke while out of my sight. Does that mean you’re in a superposition of “alive” and “dead” like Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger’s Cat?

Let me answer this as a quantum information theorist might [2]. The smallest piece or bit of information is obtained from a measurement with a binary outcome. Therefore, measuring the cat and finding it is either “alive” or “dead” constitutes a bit of information. If the cat is definitely in one state or the other inside the box and we’re just opening the box to find out which it is, then we have a classical bit of information (Cbit). If, on the other hand, the cat is truly in a superposition of “alive” and “dead”, then we have a quantum bit of information (qubit or Qbit). Let explain the difference between a Cbit and a Qbit and let you decide.

In the lingo of quantum information theory, you can get from a pure state to another pure state continuously through other pure states for a Qbit, while you are only passing through mixed states between pure states for the Cbit. As Hardy pointed out in Quantum Theory From Five Reasonable Axioms:

Axiom 5 (which requires that there exists continuous reversible transformations between pure states) rules out classical probability theory. If Axiom 5 (or even just the word “continuous” from Axiom 5) is dropped then we obtain classical probability theory instead.

Now let me explain what that means.

Suppose your Cbit is a box and a measurement of the box (opening it) reveals one of two outcomes: a ball (yes) or no ball (no). The probability space has two axes, one represents “yes” and the other “no”. Those are pure states, i.e., they represent actual measurement outcomes of a single trial of the experiment. Any state between those pure states, e.g., 80% yes and 20% no, does not represent the outcome of some new measurement, it represents a distribution of the yes-no outcomes of the original measurement, i.e., it’s a mixed state. But, if the ball-box combo was a Qbit, then that 80-20 state would have to correspond to the outcome of some other measurement with 100% probability.

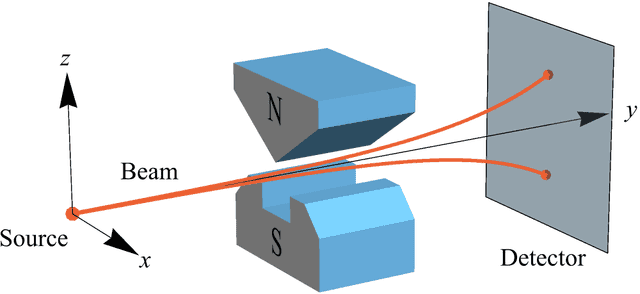

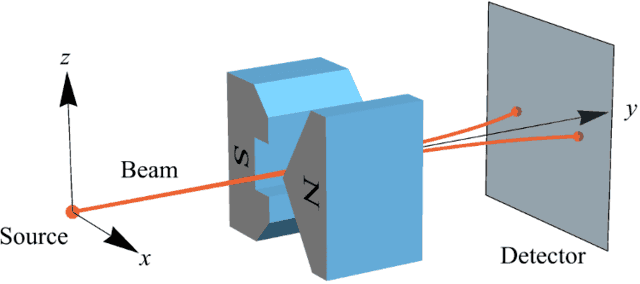

For example, consider the Qbit for electron spin. When you send electrons through a North-South magnetic field the electrons are deflected an equal degree towards the North pole (called spin “up”) or the South pole (called spin “down”). Suppose your N-S magnetic field is vertically oriented (along the z axis) and 50% of your electrons are deflected up (“up” towards the North pole) and 50% are deflected down (“down” towards the South pole) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 (taken from [2])

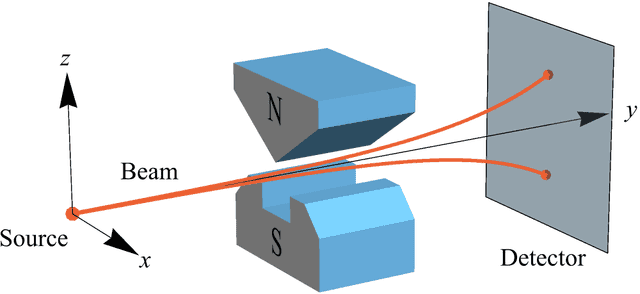

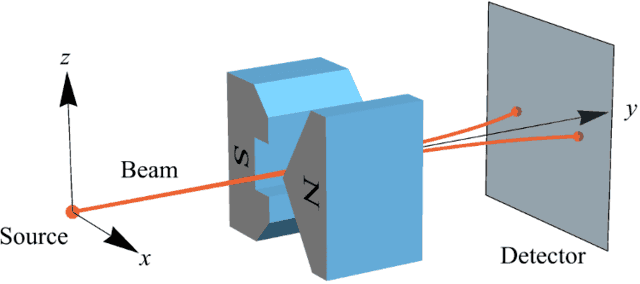

The corresponding quantum z-spin state is $$|\psi\rangle = \frac{|\text{z+}\rangle + |\text{z-}\rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$$ It means you will get 50% “up” results and 50% “down” results when you make a z-spin measurement of electrons in this state. Since this is a Qbit, your electron state must also be a pure state for some measurement corresponding to an outcome with 100% probability. What is that measurement and its outcome in this case? An x-spin “up” state works. In other words, if you first pass electrons through horizontally oriented magnets (rotate North pole ##90^\circ## to x direction in Figure 2) and let those electrons that are deflected right (“up” towards the North magnetic pole) be the Source for the vertically oriented magnets in Figure 2, then 50% will be deflected “up” (literally up for the magnets in Figure 2) and 50% will be deflected “down” (literally down). That is what it means to say your 50-50 z-spin electrons are 100-0 x-spin electrons. In quantum mechanics we write $$|\psi\rangle =|\text{x+}\rangle = \frac{|\text{z+}\rangle + |\text{z-}\rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$$ So, if you measure ##|\psi\rangle## in the z direction, you get 50% “up” and 50% “down” electrons (half of the electrons are deflected up and half are deflected down), but if you measure that same ##|\psi\rangle## in the x direction (Figure 3), you get 100% “up” electrons (all of the electrons are deflected to the right, so ignore the beam going to the left in Figure 3). Now you understand the physical difference between a Cbit and a Qbit.

Figure 3 (taken from [3])

The problem with the way most people present Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger’s Cat is that they only talk about a measurement with outcomes of Live Cat (LC) and Dead Cat (DC). Given only that information we could have a Cbit, i.e., no superposition. The problem Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger was pointing out is that quantum mechanics is supposedly applicable to anything. Therefore, it should be possible to render the Cat-Box system a Qbit rather than a Cbit in which case the state $$|\psi\rangle = \frac{|\text{LC}\rangle + |\text{DC}\rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$$ must represent the outcome of some measurement with 100% certainty. What is that measurement? And, what does its outcome mean physically? Is the Cat-Box system a Qbit simply because of its quantum trigger mechanism for the deadly gas? Does that help answer the questions we need answered to understand the Cat-Box system as a Qbit? We could answer those questions for the spin of an electron, but his point was we have no answers for the Cat-Box system. So, is quantum mechanics really applicable to any thing? Is Schr##\ddot{\text{o}}##dinger’s Cat a Qbit or a Cbit?

- E. SCHRÖDINGER, The present situation in quantum mechanics, Naturwissenschaften, 23 (1935), p. 807–812.

- W.M. Stuckey, Michael Silberstein, and Timothy McDevitt, “Einstein’s Entanglement: Bell Inequalities, Relativity, and the Qubit” (Oxford UP, 2024).

- W.M. Stuckey, “Quantum information theorists are shedding light on entanglement, one of the spooky mysteries of quantum mechanics,” The Conversation, 30 July 2024.