The recent publication of the University of Edinburgh’s Review of Race and History has drawn attention to its “skull room”: a collection of 1,500 human craniums procured for study in the 19th century.

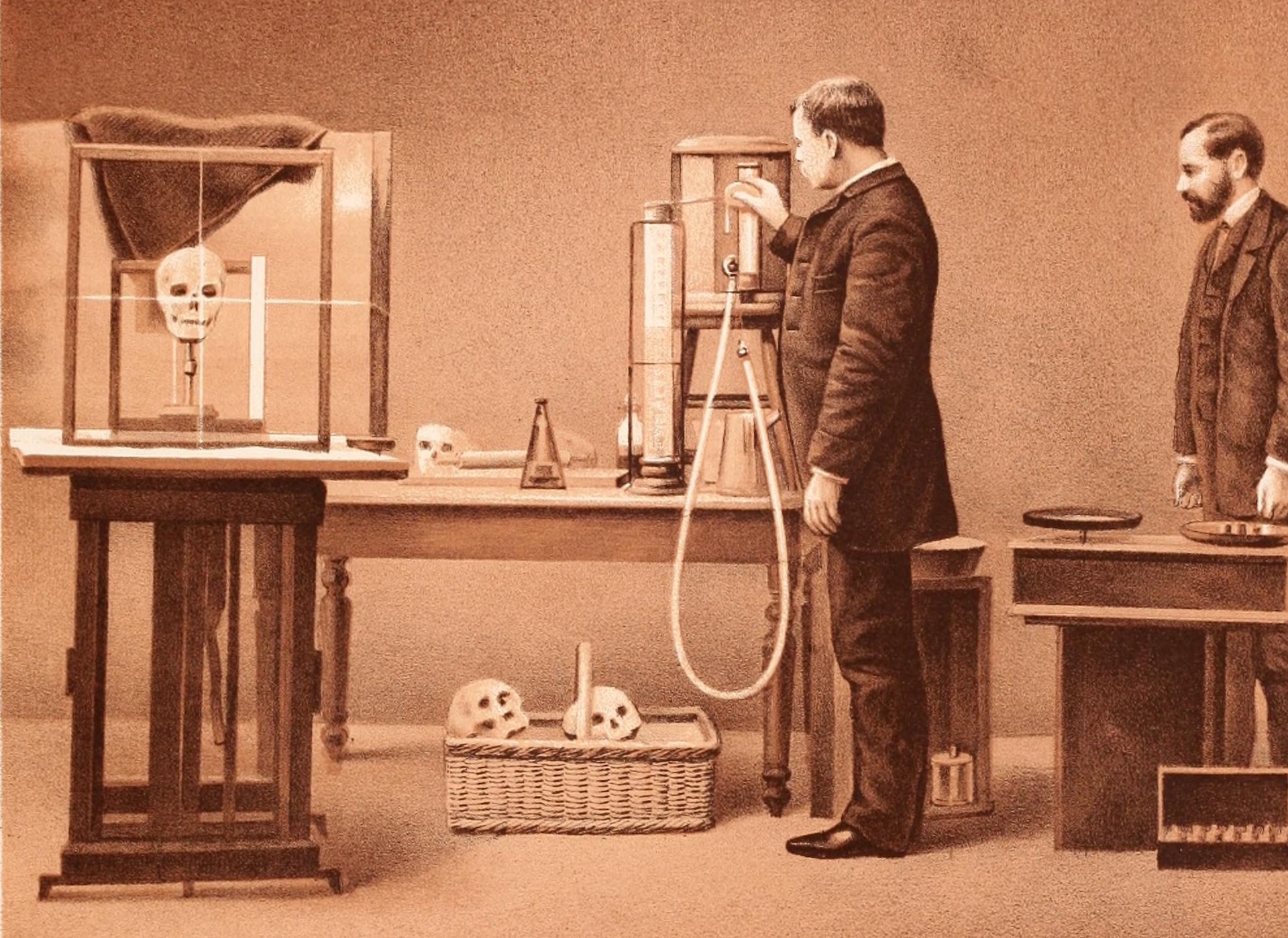

Craniometry, the study of skull measurements, was widely taught in medical schools across Britain, Europe, and the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, the harmful and racist foundations of craniometry have been discredited. It’s long been proven that the size and shape of the head have no bearing on mental and behavioral traits in either individuals or groups.

In the 19th and early 20th century, however, thousands of skulls were amassed to enable research and instruction in scientific racism. Edinburgh’s skull room is by no means unique.

Unlike phrenology, a popular theory which linked personality traits to bumps on the head, craniometry enjoyed widespread scientific support in the 19th century because it revolved around data collection and statistics.

Related: What’s the difference between race and ethnicity?

Craniometrists measured skulls and averaged the results for different population groups. This data was used to classify people into races based on the size and shape of the head. Craniometrical evidence was used to explain why some peoples were supposedly more civilized and evolved than others.

The vast accumulation of data drawn from skulls appealed to Victorian scientists who believed in the objectivity of numbers. It equally helped to validate racial prejudice by suggesting that differences among peoples were innate and biologically determined.

Medical history

The study of skulls was central to the development of 19th-century anthropology. But before anthropology was taught at British universities, markers of supposed racial difference were studied by anatomists skilled in identifying minute differences in skeletons. The study of skulls entered the university curriculum through medical schools, and particularly through anatomy departments.

For example, when Alexander Macalister was appointed as professor of anatomy at Cambridge in 1884, some of his first lectures were on “The Race Types of the Human Skull.”

Macalister’s annual report for 1892 in the Cambridge University Reporter describes how he had increased Cambridge’s cranial holdings from 55 to 1,402 specimens. In 1899, he reported the donation of more than 1,000 ancient Egyptian craniums from the archaeologist Flinders Petrie. Much of Macalister’s skull collection remains housed in the university’s Duckworth Laboratory, which was established in 1945.

As the prestige of craniometrical research increased, institutions had to compete for cranial collections as they went on the market. Statistical accuracy depended on vast series of craniums being measured to produce representative “types”. This created an increased demand for human remains.

In 1880, the Royal College of Surgeons purchased 1,539 skulls from the private collection of Joseph Barnard Davis. This was added to their existing cache of 1,018 craniums to create Britain’s largest craniological collection. This collection was largely destroyed in 1941 when the college building was bombed during world war two. The remaining skulls are no longer held by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Oxford’s University Museum of Natural History included rows of crania in their anatomical displays in the 19th century, as did the University of Manchester’s medical school (the medical school is no longer on the same site). This investment in skulls ensured that racial researchers had enough material to study and use in their teaching.

Catalogues kept by universities in the 19th and early 20th centuries reveal not only the size of their skull collections, but also the origin of individual specimens.

Historical trauma

Some medical schools, such as Edinburgh’s, repurposed skulls procured by phrenological societies earlier in the century to enhance their holdings. Others, including Oxford’s, made use of skulls unearthed by archaeologists to conduct racial research into the country’s past. This research attempted to trace the movements of Celts, Normans, Saxons, and Scandinavians across the British Isles.

Yet because craniologists wanted to capture the full extent of racial variation, skulls from abroad were especially prized. Medical graduates of British universities posted to the colonies sent foreign bones to their old professors.

In research for my forthcoming book on skull collections, I’ve found that Cambridge’s cranial register includes a skull sent from a former student stationed in India. He had plucked it from a cremation site in Bombay despite the outrage of gathered mourners. Brazen grave-robbing and colonial violence were central to the international network that furnished British universities’ skull rooms.

The racist ideology that spurred the collection of skulls 150 years ago has been completely discredited. However, some anthropologists believe these bones may still shed light on human origins, relations and migrations.

Yet ethical factors now equally shape institutional policies towards human remains. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford took its infamous “shrunken heads” off display in 2020.

Increasingly, universities and museums have confronted the historic injustices and inter-generational trauma perpetuated by their retention of human remains. Since the 1970s, Indigenous groups from around the world have launched campaigns to repatriate their ancestors’ bones. Research institutions have become increasingly responsive to these requests.

In London, the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons no longer displays the skeleton of Charles Byrne, the so-called “Irish Giant”. Byrne had explicitly denied consent for his remains to be dissected and mounted before he died in 1783.

The skulls in British universities are a testament to a vast theft of human remains from almost every territory on earth. Yet they have the potential to become powerful symbols of reconciliation if their discriminatory histories are acknowledged, and remedied through their return.

A spokesperson for the Duckworth Laboratory, University of Cambridge, said:

“We, like many institutions in the UK, are dealing with the legacies and past unethical practice in assembling the collections in our care. The Duckworth Collection and the Department of Archaeology are dedicated to fostering an open dialogue and building robust relationships with traditional communities and other stakeholders. This commitment is seen as an integral part of a continuous, reciprocal exchange of knowledge, perspectives, and cultural values. The aim is not only to address past inequities but also to enrich contemporary academic and cultural understanding through a respectful and equal partnership. In this vein, the Duckworth Collection is actively expanding its work with archival documentation and improving our records and database. In essence, the Duckworth Laboratory’s approach to repatriation and community engagement is marked by a commitment to openness, inclusivity, and a recognition of the need for an ongoing dialogue.”

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

6 Comments

https://shorturl.fm/sASCF

https://shorturl.fm/3nTew

https://shorturl.fm/9ILmL

https://shorturl.fm/zyNiL

https://shorturl.fm/CZ31v

https://shorturl.fm/Beor8