Millions of people worldwide take beta blockers to reduce the risk of cardiovascular problems, especially after a heart attack.

But two new studies suggest that for many patients, these drugs may no longer be helpful – and in some cases, they could even be harmful.

Beta blockers work to lower heart rate and blood pressure, reducing the oxygen demands of the heart. Traditionally, they’ve been prescribed after a heart attack (myocardial infarction) to give the heart time to heal and reduce the risk of a second attack.

Related: Heart Cancer Strikes Very Rarely. An Expert Reveals Why.

Here’s the catch: since beta blockers were introduced more than four decades ago, modern medical care approaches (including stents and statins) have dramatically improved recovery after a heart attack.

Today, many hearts rebound better than they once did. For women whose hearts recover well, the new research suggests that beta blockers may do more harm than good – increasing the risk of cardiovascular issues and even death.

“Beta blockers have long been a foundational treatment after acute myocardial

infarction; their use was initially supported by the results of early randomized trials,” write the researchers in one of their published papers.

“However, these trials were conducted in an era that predates what is now modern standard care.”

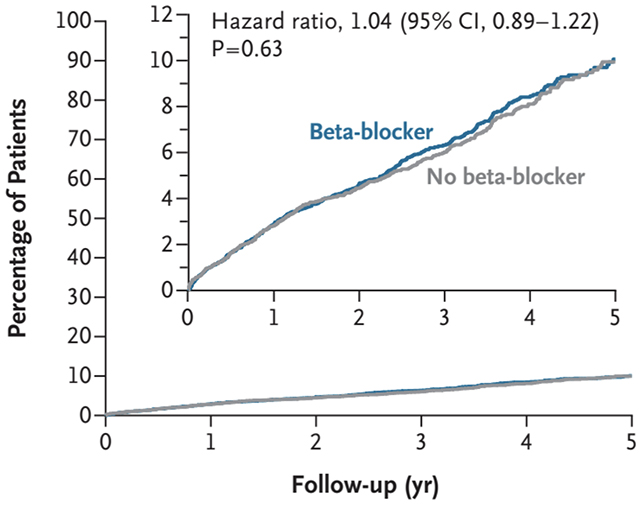

To test whether beta blockers still make sense today, scientists in Spain and Italy studied 8,438 patients across 109 healthcare centers who had survived a heart attack and had a left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) above 40 percent.

A normal EF – a measure of how efficiently the heart pumps blood– is 55–70 percent; below 40 percent indicates significant dysfunction.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>Roughly half of the patients were treated with beta blockers in addition to standard care, while the other half were not.

After an average of 3.7 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference between these groups in rates of a second heart attack, hospitalization for heart failure, or death.

The researchers then ran the numbers on just the 1,627 women – a group who were older, had more comorbidities, and received fewer guideline-based therapies.

Women on beta blockers actually fared worse, with higher risks of complications and death. The risk was greatest in women whose hearts had recovered the best and in those taking the highest doses. This pattern did not appear in men.

The researchers emphasize that beta blockers still have roles in treating other conditions, such as arrhythmia and high blood pressure.

It may take time for medical guidelines to be revised, but they hope to see a more individualized approach to beta-blocker use in the future – particularly for those whose hearts have recovered well, which is the majority nowadays.

“These results will help streamline treatment, reduce side effects, and improve quality of life for thousands of patients every year,” says cardiologist Borja Ibáñez, from the National Centre for Cardiovascular Research in Spain.

The research has been published in The New England Journal of Medicine and the European Heart Journal.

5 Comments

https://shorturl.fm/Bh1lq

https://shorturl.fm/5EU1p

https://shorturl.fm/Q7fS6

https://shorturl.fm/Qf4gW

6y2v0u