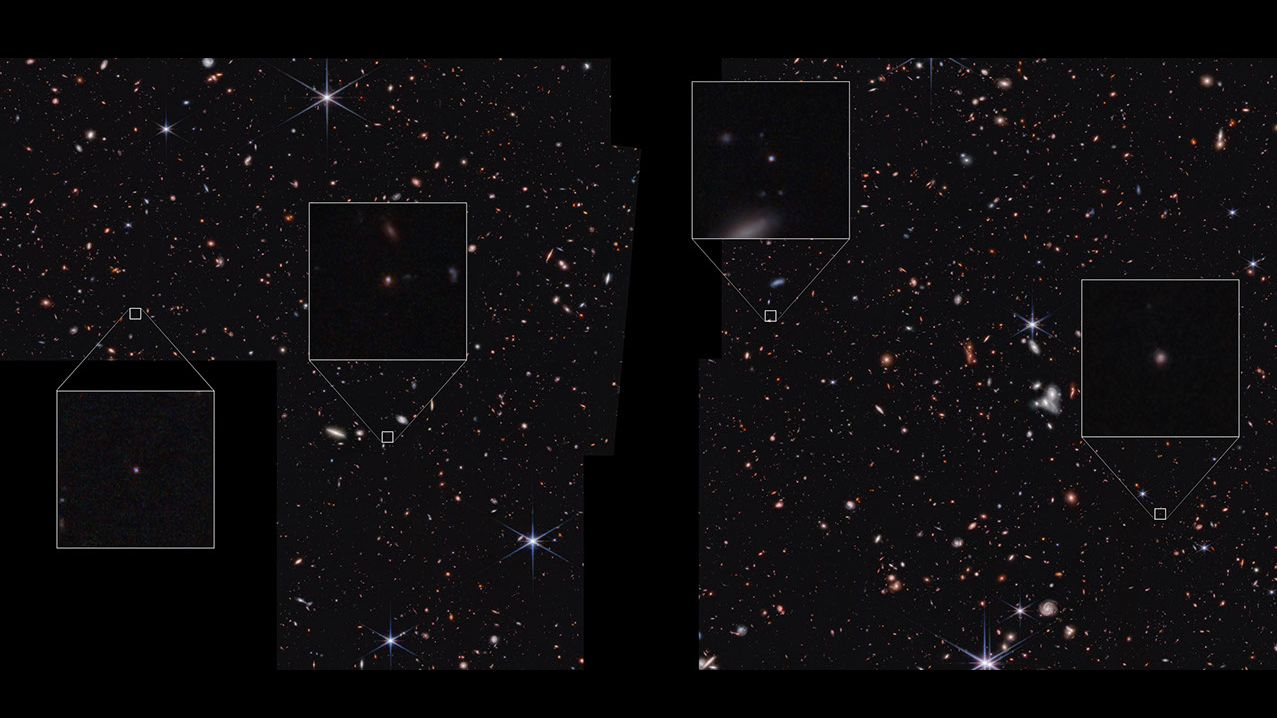

A new category of space objects dubbed “platypus galaxies” is defying explanation.

These nine strange cosmic objects, spotted in archival data from the James Webb Space Telescope, cannot easily be characterized by their features. They are small and compact, but they don’t appear to host active supermassive black holes or to be quasars, enormous black holes that glow as brightly as galaxies, according to new research.

Researchers have dubbed the cosmic oddballs “platypus galaxies” because, like platypuses — rare egg-laying mammals — they are difficult to classify, Haojing Yan, an astronomer at the University of Missouri who led the team, said when presenting the findings at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix this week.

“The detailed genetic code of a platypus provides additional information that shows just how unusual the animal is, sharing genetic features with birds, reptiles, and mammals,” Yan said in a statement describing the research, which is available as a preprint via arXiv. “Together, Webb’s imaging and spectra are telling us that these galaxies have an unexpected combination of features.”

Looking at this collection of galaxy characteristics, he added, is like looking at a platypus. “You think that these things should not exist together, but there it is right in front of you, and it’s undeniable,” he said.

For example, typical quasars — which are extremely luminous and energetic objects — have emission lines in their spectra that look a bit like hills. The spectra also indicate that gas is circulating quickly around a supermassive black hole in the center.

Yet the nine newfound galaxies have narrow and sharp spectra, signaling that the gas is moving more slowly. Although some galaxies with narrow and sharp spectra have supermassive black holes in their centers, unlike that group, the new galaxies don’t look like “points” in the images.

So if the mysterious objects aren’t quasars and they don’t host supermassive black holes, what are they? One possibility is that they represent a newly found type of star-forming galaxy that populated the early universe, which JWST is optimized to see.

But even that possibility is confusing the team, co-investigator Bangzheng Sun, a graduate student at the University of Missouri, said in the same statement.

“From the low-resolution spectra we have, we can’t rule out the possibility that these nine objects are star-forming galaxies,” Sun said. “That data fits. The strange thing in that case is that the galaxies are so tiny and compact, even though Webb has the resolving power to show us a lot of detail at this distance.”

If that’s the case, it may be that JWST is looking at a type of even earlier galaxies than have ever been spotted. If that is indeed what JWST is seeing, Yan said, perhaps there is more to learn about how galaxies evolved.

“I think this new research is presenting us with the question, how does the process of galaxy formation first begin?” Yan said. “Can such small, building-block galaxies be formed in a quiet way, before chaotic mergers begin, as their point-like appearance suggests?”

The team said they will need more galactic samples to further the research. Luckily, JWST is still early in its observing lifetime. The telescope launched in 2021 and is expected to last at least another 15 years in its deep-space position, gazing at faraway objects in the early universe.