A recent change to the definition of dyslexia put forth by an international group of researchers and practitioners could influence policy decisions that determine which children are identified as having the reading disability.

Dyslexia, a neurobiological condition that affects how individuals read and spell, has come into the spotlight in K-12 schools over the past decade. In large part, the result of growing parent advocacy, 34 states now require that schools screen children for dyslexia in early elementary school.

Now, the influential International Dyslexia Association has revised the definition of the reading disability in a way that may affect how some states operate their screening process—deleting language from its 2002 definition that refers to dyslexia as “often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities.”

Dyslexia isn’t linked to intelligence, and children who have the condition can still—and often do—succeed academically. As researchers started studying the disability in the 1960s and ‘70s, they identified students as dyslexic when their poor reading skills couldn’t be explained by their general intelligence, as measured by IQ tests.

This gave way to a method of diagnosing dyslexia that’s still popular today, called the discrepancy model, through which children are identified as dyslexic if there is an unexpected gap between their intellectual abilities and their reading performance.

But an established and growing body of evidence shows that this model may be leaving a lot of dyslexic students undiagnosed, said Charles Haynes, an emeritus professor at the MGH Institute of Health Professions, a university in Boston focused on health sciences, and the co-chair of the steering committee for the new definition.

“More than 20 years of research have indicated to us that people with below-average IQs can demonstrate word-reading and spelling difficulties that don’t differ substantially in their character from people who are of average or superior IQ,” he said.

That means that students can still be dyslexic, even without an “unexpected” gap between their scores on cognitive tests and their reading performance.

“The idea of having this cut point of a discrepancy really misrepresents the way dyslexia works,” said Devin Kearns, a professor of early literacy at North Carolina State University at Raleigh, and the chair of the IDA’s scientific advisory board.

The IDA doesn’t set state or national policy. But it has a large influence in the field, and removing this language could prompt changes in how schools identify students, said Nicole Fuller, the associate director of policy and advocacy at the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

“It does take time for research to translate to practice,” she said. “But I do think it does mark a shift.”

How schools identify students with dyslexia

Federal law on specific learning disabilities, which covers dyslexia, prevents states from requiring that schools use evidence of a “severe discrepancy” to determine whether a child has the reading disorder.

But states can allow schools to use it, and most do. As of the 2019-20 school year, 40 states reported letting districts use this method as part of their approach to identifying students with dyslexia, according to federal survey data. (Four of those states reported plans to end this policy during the 2020-21 school year.)

If those policies prevent students with average or below average IQs from receiving reading support, “that’s a civil rights issue,” said Kearns. Reporting from Scientific American and the Hechinger Report has shown that some students have been shut out of dyslexia services this way—and that the consequences disproportionately affect children of color, English learners, and children from low-income families.

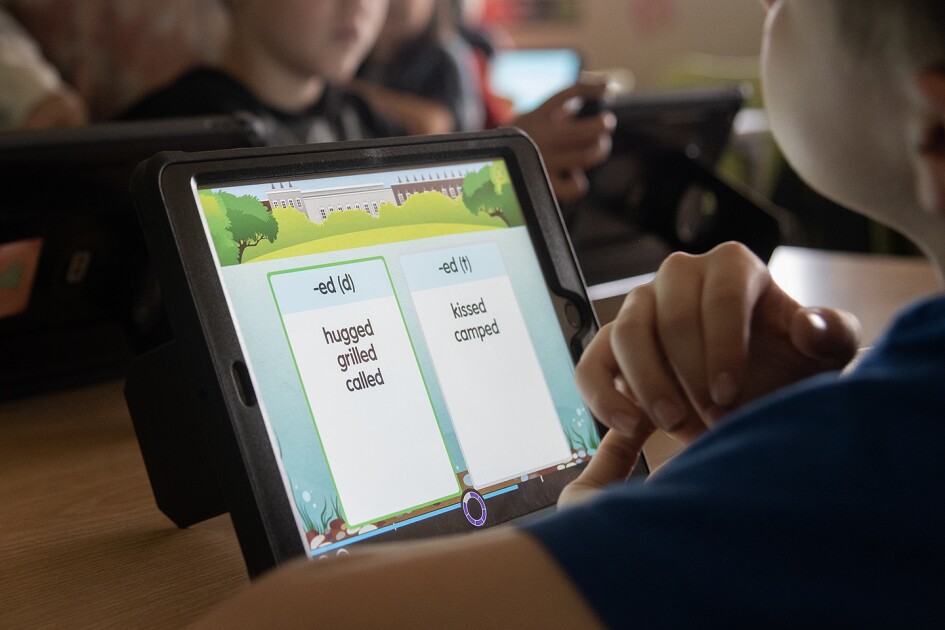

Instead of using cognitive testing to identify students, schools can give tests of the skills that are affected by dyslexia, like phonological skills and the ability to read real and nonsense words, said Kearns.

Many schools use the response to intervention method, or RTI, to identify who might need to be evaluated for dyslexia. Students who need academic support outside of what they get in their general classroom settings have access to multiple “tiers” of interventions, depending on how severe their needs are.

“If there’s a really strong early intervention program, then that’s really good. But that’s not always the case,” said Nancy Mather, an emeritus professor of disability and psychoeducational studies at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

A 2015 federal evaluation of RTI found that 1st graders who received reading interventions did worse than similar peers who didn’t.

‘Discrepancy’ model remains popular in some quarters

A few prominent voices in the dyslexia community are pushing back against IDA’s decision to remove references to dyslexia being “unexpected,” arguing that encouraging states to drop cognitive discrepancies could introduce new problems into the identification process.

“They’re setting up a system where you’re going to exclude kids,” said Bennett Shaywitz, the co-director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity.

Gifted students with dyslexia might surpass cutoff points on tests of reading skills, but still be performing much lower than they could with dyslexia-specific support services. Examining the gap between intelligence tests and reading ability helps pinpoint those students, Shaywitz said.

Language about dyslexia being an “unexpected” reading difficulty is also embedded in the 21st Century Dyslexia Act, a bill sponsored by Republican Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana that would establish a standalone category for dyslexia in federal disability law and provide equal access to accommodations for all students.

Haynes, the co-chair of the IDA definition steering committee, said that including this language in the bill is a “mistake.”

In response to a request for comment, an aide for the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, or HELP, committee, wrote in an emailed statement that the definition “hinges on the word unexpected.”

“There are some children for whom a reading difficulty is expected. For example, a child who has had an accident and suffered brain damage. In this case, the reading difficulty is expected, and this child would not benefit from a specific intervention to address dyslexia.

“This is one condition among other conditions in which an intervention for dyslexia would not be beneficial,” the aide said.