Mary K. Gaillard, a theoretical physicist whose calculations of the properties of new elementary particles helped validate the Standard Model of physics in the 1970s, died on May 23 of natural causes at her home in Berkeley. A UC Berkeley professor emerita of physics and faculty senior scientist emerita at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, she was 86.

Gaillard knew she wanted to be a physicist since she was a teenager and pursued that dream despite the fact that women in the 1960s and ’70s were not always welcome in the field. Following her physicist husband to Paris, France, in 1961, she set out to pursue her doctorate, but was rejected as a graduate student by numerous male scientists who told her that women could not do physics.

In 1964, after her husband took a six-year appointment at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) — Europe’s main hub of high energy particle physics — she eventually found a mentor at the University of Paris in Orsay, France, now Paris-Saclay University. While raising three children, she dove into the theory of elementary particles and worked on her second doctoral thesis, which she defended in 1968 — two months after the birth of her third and last child. She remained a visiting scientist at CERN until 1981, when she moved to UC Berkeley.

“I was motivated all the time by loving physics and enjoying doing physics,” Gaillard told UC Berkeley News in 2015. “There was a time in my life when I was being a mother, cooking dinner, washing and doing physics and not much else. But it never occurred to me to give up. It was something I loved.”

“My memories of my mother include her constantly writing formulas, even on the weekends,” said her daughter, Dominique Gaillard, who was born during the period her mother was writing her first doctoral thesis.

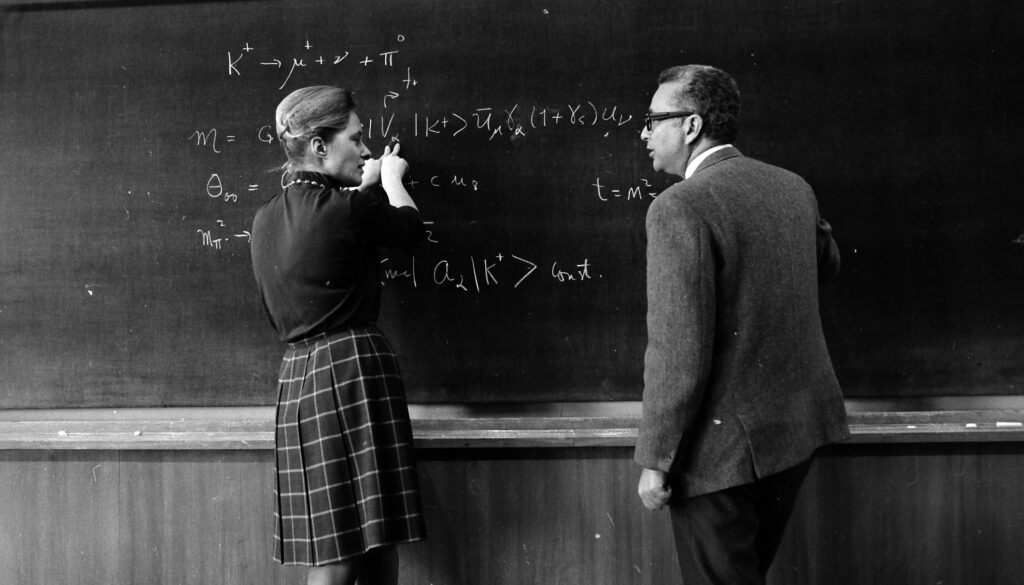

Courtesy of CERN

The 1960s and ’70s were a time of foment in the field of physics. Particle accelerators like those at CERN in Switzerland and at Fermilab, Brookhaven, Berkeley and Stanford in the U.S. were finding scads of new particles, and physicists had come up with innovative theories to explain their existence. In the early 1960s, Murray Gell-Mann proposed a novel way of classifying some of the new particles — the hadrons, which are held together by the strong force — for which he earned the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physics. He and others eventually proposed the existence of smaller fundamental particles called quarks to explain these relationships. Gell-Mann also introduced the idea of symmetries in nature to make predictions from the theory. Symmetries underlie today’s Standard Model of particle physics, which links the strong, weak and electromagnetic forces.

“People had no real theory in the ’60s to describe the strong nuclear interaction. What is it that binds protons and neutrons in nuclei?” said Lawrence Hall, a UC Berkeley professor of physics and colleague of Gaillard. “Gell-Mann came up with this idea that he could understand the pattern of the different hadrons — the proton, the neutron, the lambda, the sigma, all of these particles that they discovered — if there were quarks inside. But people didn’t know whether that was just some bookkeeping device or whether these quarks were going to be for real.”

Gaillard wielded the new calculational tools to predict, mathematically, the properties of new particles, such as their masses, spins and their modes of decay. She talked frequently with CERN experimentalists in order to decide which projects to tackle.

“She was one of the early believers in the quark theory before most people had cottoned on,” Hall said. “She was one of the first people actually doing these calculations, figuring out how a K-meson, or kaon, would decay, for example.”

“She was certainly a pioneer in applying the calculations to phenomenology to actually make predictions,” said John Ellis, with whom Gaillard collaborated on 45 papers. Two of them have been cited more than 1,000 times, which is unusual for a theory paper.

Dominique Gaillard

Mary K, as she was known, was a visitor in the theory division at CERN from 1964 — the year she received her first doctorate (Doctorat de Troisième Cycle) from Orsay — until she moved to UC Berkeley in 1981. Unlike many male physicists, however, she was never offered a paid staff position. According to her long-time friend, experimental physicist Nan Phinney, CERN did not offer salaried positions to women, assuming that they had a husband to support them. Nevertheless, Gaillard shared offices — initially in the basement — with like-minded physicists and interacted with them as equals, mentoring students both male and female.

“She was very supportive of other women in the field and took us under her wing,” said Phinney, who is now at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center but was a graduate student when she first met Gaillard in 1972.

In 1980, Gaillard wrote a “Report on Women in Scientific Careers at CERN” that addressed the issue of inequality — only 3% of CERN’s regular research staff were women — and called for equality in promotion, maternity leave and provision of a full-day day-care center. Fourteen years later, in 1994, CERN finally appointed a woman scientist to a senior position. That woman, Fabiola Gianotti, became CERN’s director-general in 2016.

“Mary K was a theoretical physicist of great power, gifted with both deep physical intuition and a very high level of technical mastery,” her colleague Michael Chanowitz, a faculty scientist at Berkeley Lab, wrote in a memorial. “She pursued her love of physics with powerful determination, in the face of overt discrimination that went well beyond what may still exist today. She fought these battles and produced beautiful, important physics while raising three children as a devoted mother.”

Pursuing charm

After her second doctorate (Doctorat d’Etat) from Orsay in 1968, she was offered the equivalent of an assistant professorship at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), though she remained an unpaid scientific associate during most of her time at CERN.

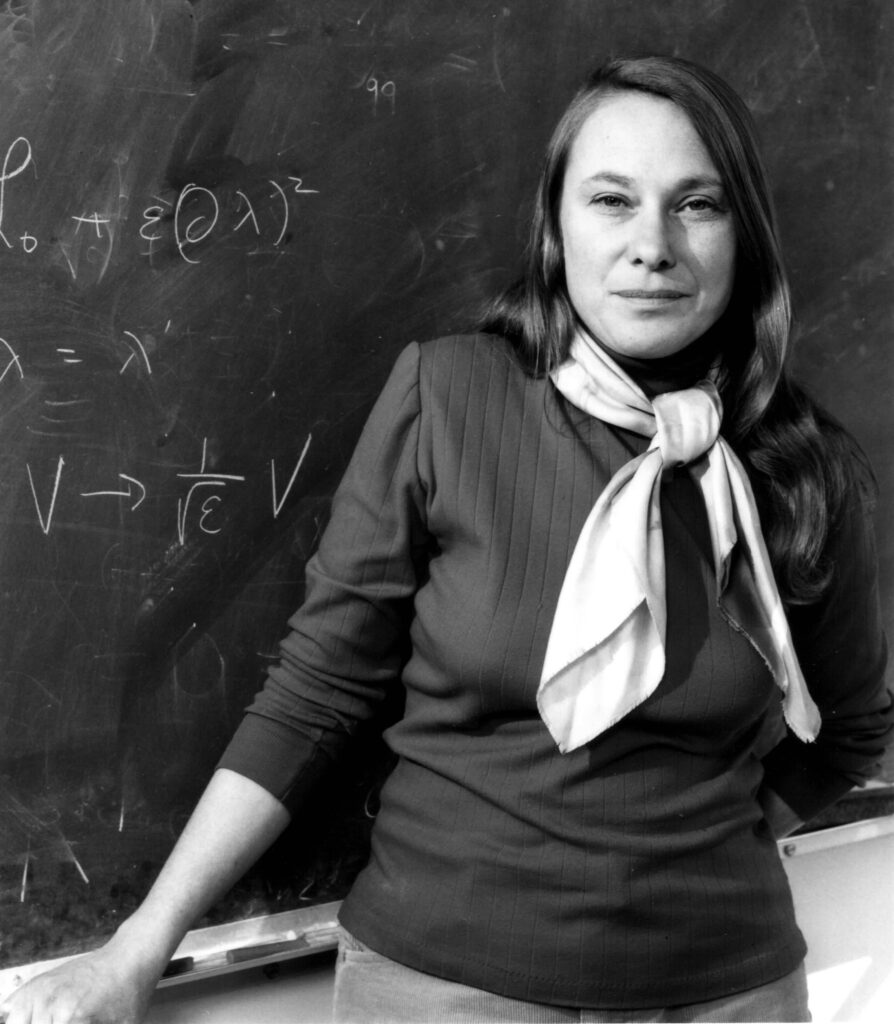

Courtesy of Fermilab

Ellis, now at King’s College, London, first met Gaillard at CERN in 1974, soon after he had arrived as a postdoctoral fellow and she had just returned from a sabbatical year at Fermilab in Illinois, where she had written an influential paper predicting the mass of the charm quark based on the theory known as quantum chromodynamics (QCD).

“When we did meet, of course, she’d already established a strong reputation, in particular, her work with Ben Lee on the weak interactions of kaons and the constraints that they imply on the mass of the charm quark,” Ellis said. “Her prediction for the mass of the charm quark was confirmed by the discovery of charmonium,” a bound state of a charm quark and an anticharm quark.

Their first notable collaboration, in 1975, involved the Higgs boson, the existence of which was a key prediction of gauge theories of the weak interaction, the main force involved in particle decay. Gaillard, Ellis and Dimitris Nanopoulos wrote a detailed study of what the Higgs boson would look like in different experiments, “so that they would know what they might be finding if they were to find anything,” Ellis said.

“One of the things that we calculated in that paper was that the Higgs boson should decay into two photons through quantum effects,” he said. “And that decay was one of the key discovery modes when the Higgs boson was discovered in experiments at CERN in 2012. Mary K was certainly the leader in our calculations.”

Peter Higgs and François Englert shared the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics for their original theory of the Higgs boson — what some called the “God particle.”

UC Berkeley

In a 1976 paper, working with the late Graham Ross, Gaillard and Ellis described an experiment that would prove the existence of another hypothetical particle, the gluon, which mediates the strong force that holds nuclei together, similar to how the photon mediates electromagnetic interactions. Three years later, physicists conducted that experiment and discovered it, as predicted. Gaillard and Ellis also explored grand unified theories, or GUTs, that combine strong, weak and electromagnetic forces. In 1977, they teamed up with Chanowitz to write and circulate a paper that predicted the mass of the bottom quark, which was found to be correct even before the paper was officially published.

Lawrence Hall, a UC Berkeley professor of physics, said that the flurry of papers Gaillard, Ellis and their collaborators produced were the go-to source for what was happening in the field of elementary particle physics at the time.

“Ellis and Gaillard had this fabulous collaboration going and I knew it at the time because in the late ’70s I was a graduate student, and that’s where I was learning what all the exciting stuff was. I was reading all the Ellis-Gaillard papers,” he said. “The ‘70s was this amazing era in the field, and Mary K was one of the leaders, right there in the thick of it.”

Gaillard was invited to join the UC Berkeley physics faculty in 1981, after agitation by women graduate students to hire a female faculty member. Gaillard was the department’s first woman professor and the first woman to receive tenure.

A singularly unfeminine profession

Mary Katharine Ralph was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey, on April 1, 1939, the only daughter of Philip Lee Ralph, a historian at Rutgers University, and Marion Ralph (née Wiedmayer), a teacher. Her father was denied tenure because of his pacifist leanings, and the family relocated to Painesville, Ohio, near Cleveland, where he taught at a small liberal arts college. Her parents called her Mary Kay, but eventually she shortened it to Mary K, without a period.

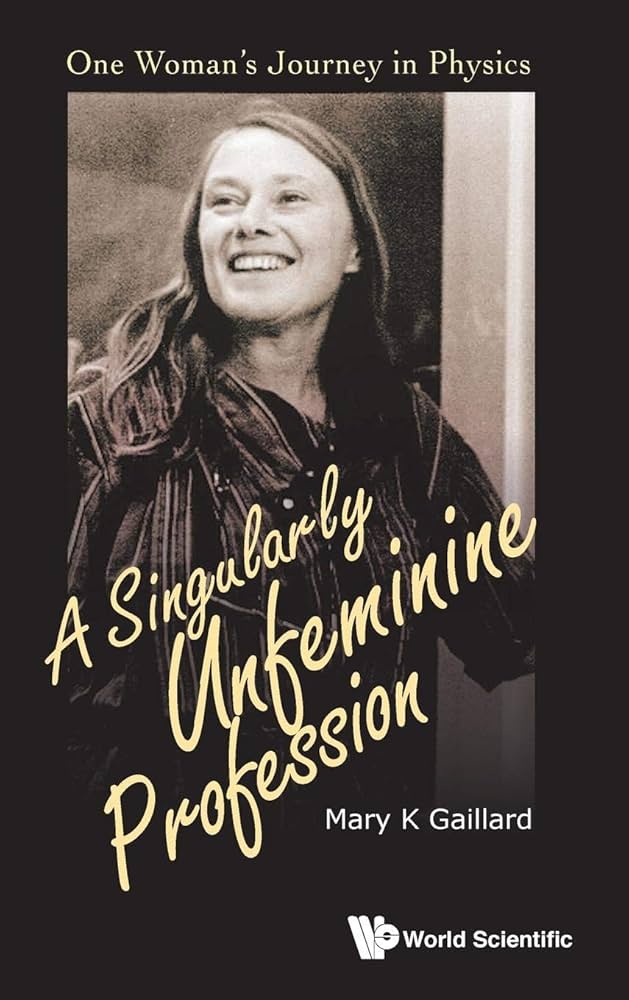

Courtesy of World Scientific press

In her 2015 memoir, A Singularly Unfeminine Profession: One Woman’s Journey in Physics, Gaillard recalled liking physics and math from an early age and getting encouragement from her teachers. The book title, she said, was inspired by an off-hand remark made by a fellow high school student after she told him she planned to pursue a career in physics.

Enrolling with a full scholarship at Hollins College (now University) in Roanoke, Virginia, she continued to receive encouragement and was recommended for two summer internships at Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, where she got hooked on particle physics. There she also met her future husband, Jean-Marc Gaillard, at the time a French postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University. After graduation in 1960, Mary K applied and was accepted to Columbia, but after a year she married Jean-Marc and moved to France in 1961. There, she enrolled as a graduate student at Orsay and looked around for a position in a group conducting particle theory, hoping that her master’s degree from Columbia would open doors. To her surprise, no one wanted to hire a woman as a theorist or, for that matter, as an experimentalist. She eventually found an advisor but was basically on her own and chose her own projects to work on, which suited her fine.

“I basically always directed my own research,” she told an interviewer for a 2020 oral history for the American Institute of Physics.

After obtaining two doctorates from Orsay, a requirement of the European academic community at the time, she obtained an appointment as a researcher for CNRS but remained based at CERN. There, she focused initially on weak interactions, like those involved in the decay of a heavier particle into lighter particles, and how that might cause the asymmetry between matter and antimatter in the universe. She eventually moved on to strong interactions and to theories beyond the Standard Model, which try to incorporate the gravitational force in a Grand Unified Theory.

Frustrated by her unofficial status at CERN, she eventually started and led her own theory group, from 1979 to 1981, at the Laboratoire d’Annecy de Physique des Particules (LAPP), a high energy physics laboratory not far from CERN. In 1981, after being turned down again for a staff position at CERN, she accepted a job offer from UC Berkeley.

Supersymmetry

When she moved to Berkeley, she separated from her husband, and they later divorced. She had started collaborating with Bruno Zumino, one of the originators of supersymmetry — the idea that all particles have a twin with different spin. Zumino eventually followed her to Berkeley and they later married. She headed Berkeley Lab’s Particle Theory Group from 1985 to 1987.

AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives, Gift of Mary K. Gaillard

“The work that she did, certainly with Ben Lee and, dare I say it, with me and our other collaborators, was foundational for the establishment of the Standard Model,” Ellis said. “And then the work she did with Bruno Zumino was also very influential in the formulation of theories with supersymmetry.”

For the remainder of her career she focused on physics beyond the Standard Model, including supersymmetry and an extension called supergravity, string theory, and a Grand Unified Theory, which has implications for cosmology and dark matter. Supersymmetry was thought to be the most likely theory to incorporate the Higgs boson, which gives particles mass. However, the failure to find any supersymmetric particles in collisions at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider leaves its reality uncertain, according to Lawrence.

“In the ‘70s and early ‘80s, Ellis and Gaillard were among the first to study many of the great questions that we still can’t answer. Do the strong and electroweak forces unify? Is supersymmetry relevant? What governs the pattern of quark and lepton masses? What created the baryon asymmetry of the universe?” he said. “It’s really an amazing situation we find ourselves in. It’s not like the questions have disappeared. They’re still with us. They’re some of the big ones.”

Gaillard’s contributions to the field were recognized through the E.O. LawrenceAward and the J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics. She was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and a member of the American Philosophical Society. She served on several committees of the American Physical Society, advisory panels for the Department of Energy and the U. S. National Research Council, and on advisory and visiting committees at universities and national laboratories. She was a member of the National Science Board from 1996 to 2002.

Gaillard’s legacy includes not only groundbreaking research but lasting support for future generations of physicists, especially women, her daughter said. Gaillard supported young physicists internationally, co-directing the 1981 Les Houches Summer School in Theoretical Physics on Gauge Theories in High Energy Physics in France. She served on the American Physical Society’s Committee on the Status of Women in Physics (CSWP) as a member from 1983 to 1985 and as the chair in 1985. At UC Berkeley, she mentored numerous graduate students in advanced topics like supersymmetry and supergravity throughout her tenure and after her retirement. She is survived by three children — Alain in France, Dominique in Seattle and Bruno in the Bay Area — seven grandchildren and her former husband, Jean-Marc Gaillard. Her second husband, Bruno Zumino, died in 2014. Her brother, George Ralph, died in 1997.