by Terry Heick

Humility is an interesting starting point for learning.

In an era of media that is digital, social, chopped up, and endlessly recirculated, the challenge is no longer access but the quality of access—and the reflex to then judge uncertainty and “truth.”

Discernment.

On ‘Knowing’

There is a tempting and warped sense of “knowing” that can lead to a loss of reverence and even entitlement to “know things.” If nothing else, modern technology access (in much of the world) has replaced subtlety with spectacle, and process with access.

A mind that is properly observant is also properly humble. In A Native Hill, Wendell Berry points to humility and limits. Standing in the face of all that is unknown can either be overwhelming—or illuminating. How would it change the learning process to start with a tone of humility?

Humility is the core of critical thinking. It says, ‘I don’t know enough to have an informed opinion’ or ‘Let’s learn to reduce uncertainty.’

To be self-aware in your own knowledge, and the limits of that knowledge? To clarify what can be known, and what cannot? To be able to match your understanding with an authentic need to know—work that naturally strengthens critical thinking and sustained inquiry.

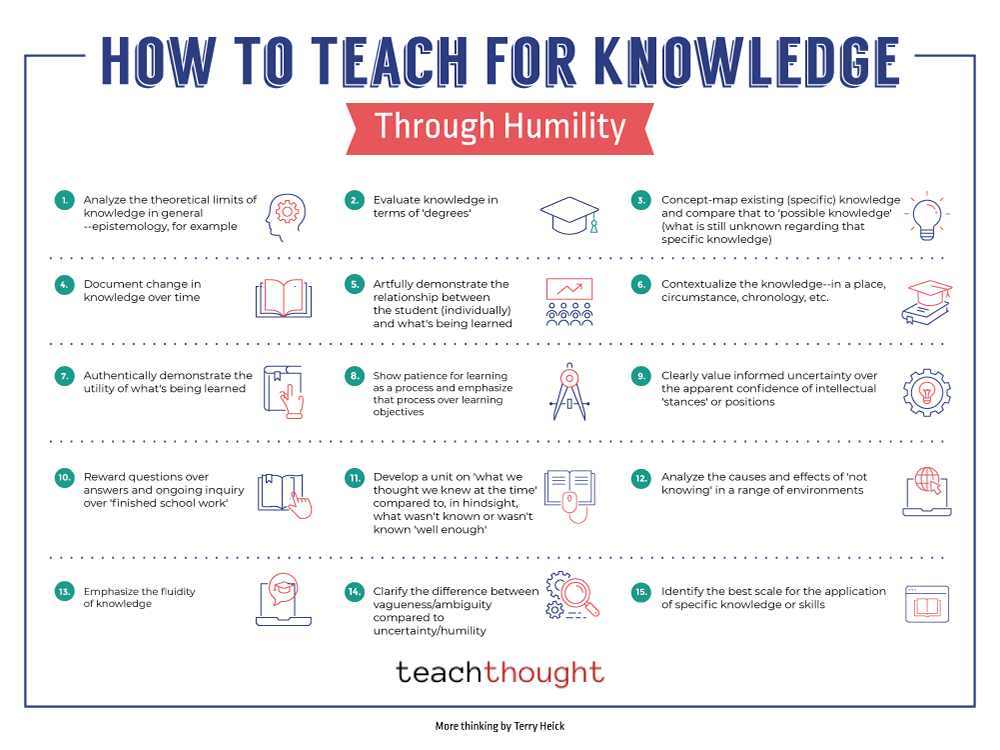

What This Looks Like In a Classroom

- Analyze the limits of knowledge in plain terms (a simple introduction to epistemology).

- Evaluate knowledge in degrees (e.g., certain, probable, possible, unlikely).

- Concept-map what is currently understood about a specific topic and compare it to unanswered questions.

- Document how knowledge changes over time (personal learning logs and historical snapshots).

- Show how each student’s perspective shapes their relationship to what’s being learned.

- Contextualize knowledge—place, circumstance, chronology, stakeholders.

- Demonstrate authentic utility: where and how this knowledge is used outside school.

- Show patience for learning as a process and emphasize that process alongside objectives.

- Clearly value informed uncertainty over the confidence of quick conclusions.

- Reward ongoing questions and follow-up investigations more than “finished” answers.

- Create a unit on “what we thought we knew then” versus what hindsight shows we missed.

- Analyze causes and effects of “not knowing” in science, history, civic life, or daily decisions.

- Highlight the fluid, evolving nature of knowledge.

- Differentiate vagueness/ambiguity (lack of clarity) from uncertainty/humility (awareness of limits).

- Identify the best scale for applying specific knowledge or skills (individual, local, systemic).

Research Note

Research shows that people who practice intellectual humility—being willing to admit what they don’t know—are more open to learning and less likely to cling to false certainty.

Source: Leary, M. R., Diebels, K. J., Davisson, E. K., et al. (2017). Cognitive and interpersonal features of intellectual humility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(6), 793–813.

Literary Touchstone

Berry, W. (1969). “A Native Hill,” in The Long-Legged House. New York: Harcourt.

This idea may seem abstract and even out of place in increasingly “research-based” and “data-driven” systems of learning. But that is part of its value: it helps students see knowledge not as fixed, but as a living process they can join with care, evidence, and humility.

Teaching For Knowledge, Learning Through Humility

6 Comments

https://shorturl.fm/IGKQ3

cy833g

https://shorturl.fm/Czzcm

https://shorturl.fm/Czzcm

znqxrx

i05jym